The Disaster

The 29th of September 2009 is remembered as the day that several Pacific Islands were devastated by the ocean’s raw power; an 8.1 magnitude earthquake struck in the Pacific Ocean, triggering a destructive tsunami that made landfall in Samoa, American Samoa, and Tonga.

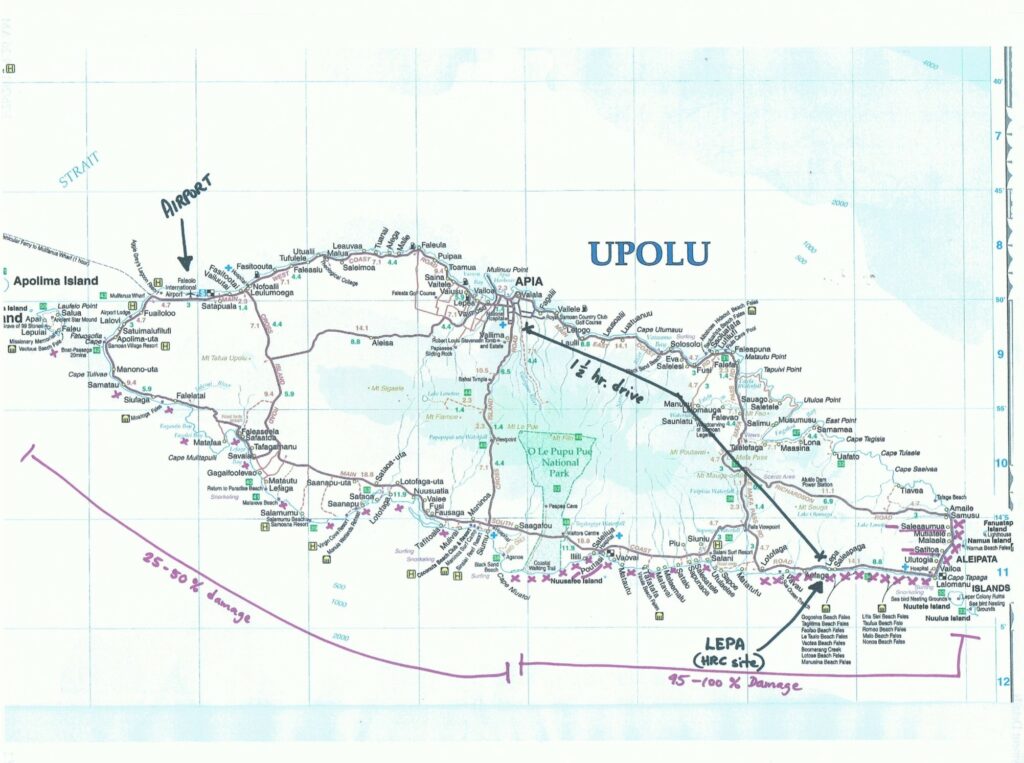

To this day, the 2009 tsunami is the worst recorded natural disaster in Samoan history; there were 149 fatalities, hundreds injured, and almost 3000 people were believed to be experiencing homelessness after losing their homes. The southern side of Upolu was struck the hardest, with 20 villages reportedly destroyed. In Lepā, only the church and the village’s welcome sign remained unaffected. Lepā became the Habitat For Humanity reconstruction and operations centre.

As the world learned of this tragedy, help for Samoa began to be rallied and Habitat for Humanity New Zealand committed to undertake our first-ever direct disaster response project to support our Pacific neighbours.

The rebuild that would follow succeeded in housing almost 100 families who lost their homes, involved more than 500 Kiwi volunteers, and sparked a project management model that is still used today.

Coastal villages on south side Upolu, Samoa, reduced to rubble and foundations by the powerful tsunami, and exposed mass substandard buildings and materials.

A planning map from the Samoa Hope Project. On this map the village of Lepā is stated to have 95%-100% damage.

The Response

The first members of Habitat New Zealand’s team landed in Samoa one week after the disaster to take stock of the local need and plan how to best improve access to shelter. O

The destruction they saw was indescribable.

“It was unbelievable. You’d see cars and light boats lodged six metres up in the air in trees. The tops of trees had died because of the salt water,” says Lou Maea, Technical Manager for Habitat New Zealand, about what he saw after arriving in Samoa, a week after the Tsunami.

Lou, the Habitat team, Digicel Samoa and Caritas Samoa, the chosen in-country partners, spent time with displaced families, assessing where the need was greatest in villages, and quickly began to plan a response. Due to the widespread devastation, we knew many hands would be needed.

With skilled volunteers from New Zealand clambering to lend a hand with the rebuild, Habitat New Zealand made renovations to an existing church hall in Lepā to house the incoming help. Guttering was added, water filtration was erected, toilet and shower blocks were built; everything from industrial cooking equipment to mattresses and the mealtime cutlery was sourced to house the workforce and enable the rebuild. Habitat also made a significant investment in all tools and equipment, and bought containers for storage, trucks, and vans for transport of volunteers and materials

Only four weeks after the tsunami made landfall in Samoa, the first volunteers had arrived on the ground and Habitat New Zealand’s first ever disaster response rebuild, the Samoa Hope Project, was underway.

Groups of 25 volunteers were brought in to build for two weeks each; the first week they would learn the tasks and processes from the proceeding volunteers, the second week they would teach the next group and so on. At any one time there were up to 40-50 volunteers building, with 43% of the total volunteer force being skilled professionals who were already working in the construction industry in New Zealand.

More than 500 volunteers turned their compassion into action by participating in the rebuild in Samoa.

Across the seven-month project that concluded in June 2010, 96 traditional Samoan fale were built in five affected villages to become homes for families affected by the tsunami. Alongside the construction of new homes, around four large community halls and churches were also built on higher ground.

Habitat New Zealand volunteers building a fale during the final month of the project. June 2010.

Completed fale. June 2010.

After the waves receded, it was observed that when the water collided with existing enclosed structures that were often built to western standards or ‘norms’ they often collapsed the immovable walls, whereas the open traditional Samoan structures allowed the water to flow over, through, and under it. In locations where the waves were less powerful, this resulted in some fales needing only minor repairs.

“That was the beauty of it, traditional building practices were the savior in that situation,” says Lou.

This highlights the importance of working alongside traditional knowledge and communities to consider the local context as Habitat implements in any work we do.

The Long-Term Impact

The families

From a place of such devastation and loss, 96 displaced families were able to rebuild a sense of home because of the Samoa Hope Project. The enduring positive impact of security and stability through shelter was invaluable in the years following the event. After receiving a fresh start, many families have been able to step into modern housing or migrate to new opportunities in the past 14 years. Habitat New Zealand continues to be proud of our outcomes and close partnership with the community during the aftermath of this event.

New ways of working

As well as being Habitat New Zealand’s first disaster response project, the scale of the rebuild and volume of workers meant that the planning and management of the project needed new processes to accommodate it. This led to the development of a new system to track construction and percentages of completion of each home. Tasks such as clearing the site, adding a septic tank, building foundations, erecting walls, securing building inspections etc. were attributed a relevant percentage.

“I knew by looking at the number, for example, that if a house was 80% completed, it was basically a finished house (roof on) without its windows, premade doors and paint,” says Lou.

Versions of this same system have been used in Habitat since this event, including during the Tonga tsunami rebuild that began in January 2022 and concluded in the past three months.

Preparing for the future

The immense construction work happening at the time was also an opportunity to upskill local Samoans, benefitting individual livelihoods and the community building knowledge for the future.

The Australia-Pacific Technical College (APTC) began a course dedicated to training a new generation of skilled workers. APTC worked closely with village councils and church ministers to select 15 students from five tsunami affected villages, Sale’a’auma, SaLepāga, Lepā, Satitoa or Poutasito, who were then enrolled in the Certificate II in Housing Repairs & Maintenance; APTC offered them a fee waiver as well as all their training equipment and uniforms.

These students worked in their own villages alongside builders and volunteers from Habitat New Zealand during Samoa Hope Project, learning practical skills and earning eligibility for further formal carpentry study at APTC if they wished.

“The community looks at us differently now because we are setting an example of how we can help ourselves,” said one student during an APTC site visit to the project.

In discussing how the project is affecting village life, loved ones of students told the trainers that “community spirit” is improving and people are starting to feel more hopeful about the future.

“Helping the men has helped us think about what is good and not just what we have lost.”

APTC students pictured working alongside Habitat New Zealand in a newsletter article sent in May 2010.

Thank you to all who made this momentous disaster response possible. This includes The Government of Samoa, Habitat for Humanity Asia-Pacific, our international volunteers, local volunteers, families and partners, and all generous donors. Without your support, this project would not have been possible.